How Paris Forgot Beauty

From Notre Dame, to the Eiffel Tower, to The Pompidou

According to a Flight Network survey, Paris was ranked as the most beautiful city in the world. It’s the city of love. A city which daily welcomes hordes of tourists hoping to experience what Hemmingway meant when he said:

“If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then wherever you go for the rest of your life it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

Paris might be humanities best attempt at urbanized beauty. As such it can be said that as Paris goes, so goes the world; for within its tourist trod streets one can trace the movement from a world in which beauty was believed to be real, to a world in which beauty became a display of achievement, and finally to a world unsure of whether beauty exists at all.

The Pre-Modern Era

Ranging from antiquity to the late 1700’s, the pre-modern era was marked by the belief that beauty is something divine. It is not created, it is discovered. Architecture therefore should be a kind of window to the divine. A portal to heaven; not so that humanity can reach God, but so that God can reach us. Famed Gothic architect Abbot Sugar explained:

“The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material, and in seeing this light is resurrected from its former submersion”.

This philosophy was made manifest in Paris’s most famous church: Notre Dame.

Embed with meaning in every detail, the cathedral not only tells a divine story, but draws the human eye upward towards the heavens. Natural light was viewed as divine, a visual sign of God’s favor. It’s flying buttresses allowed the building to retain its structural integrity while maximizing the window height so the sanctuary could be filled with natural light.

One would imagine it to have been designed by a master architect, but it was not. Instead, it was built over nearly two centuries by generations of peasants and craftsman guided by a shared understanding of beauty, meaning, and divine order.

The Modern Era

In 1789 the streets of Paris ran red with blood. The French Revolution had begun. Some of the revolutionary leaders wanted to destroy Christianity. Others wanted to reshape it into a new civic religion grounded in human reason and revolutionary ideals.

This marked the end of the pre-modern period, and the beginning of the modern period; a time that would place old superstitions under the foot of rationality and productivity.

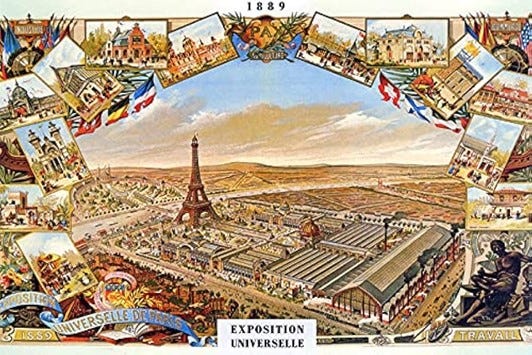

In 1889, Paris hosted the World Fair. It marked the 100-year anniversary of the French Revolution. It was a celebration of human industry, engineering, and progress; a grand fair for a world that no longer needed God.

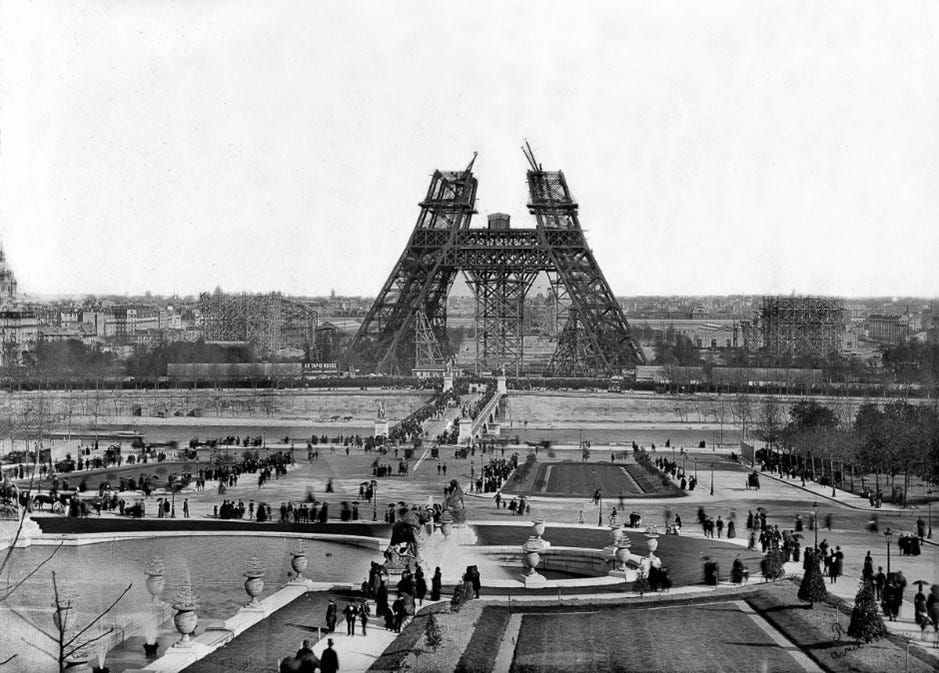

Such an event would need a grand entrance. A monument to human achievement. Some testament to the sheer power of humanity. Thus, the Eiffel Tower was constructed.

It was scheduled for removal in 1909, two decades after the fair. It was the tallest structure in the world.

Unlike Notre Dame, its construction was not guided by a philosophy of discovering beauty, but by the confidence that beauty could be created.

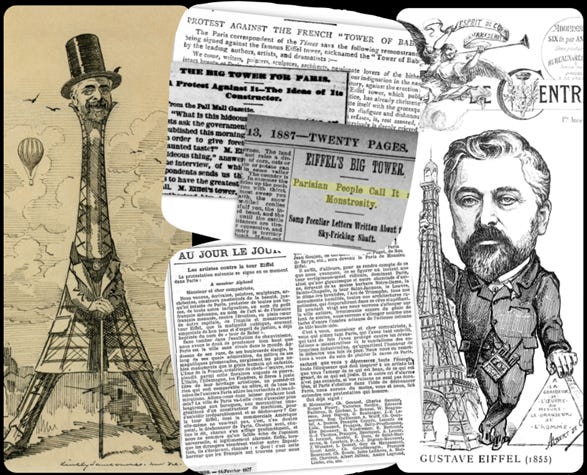

Paris’s artists, poets and architects revolted. They signed a public letter of protest condemning the tower as a “tragic street lamp”, and a “factory chimney dominating Paris”.

Among these critics were some of France’s most influential cultural voices; Guy de Maupassant, Charles Gounod, Alexandre Dumas, Charles Garnier, and Joris-Karl Huysmans.

They did not oppose engineering. They opposed what the tower symbolized. To them, it represented a break from humility- towards self-glorification.

These men were skeptical of the Revolution’s cultural consequences, especially its attempt to sever France from its pre-modern conceptions of meaning and beauty.

The Eiffel Tower was even likened to an ancient story- the Tower of Babel. A structure built not to honor God, but to turn man into God.

The tower stands today not because it was loved, but because it proved useful. It wasn’t taken down as initially planned, because it was used as a radio tower. This became invaluable to the state, especially during the events that came next.

The Post-Modern Era

The World Wars. The period from 1914 to 1945 contained both world wars, genocides, famines, and pandemics. It produced a level of mass death unprecedented in its scale and speed.

It brought the enthusiasm of the modern period to a screeching halt and shattered modernities faith in human progress. This marked the beginning of the Post-Modern Era.

Both faith in God and faith in humanity were gone. A deep cultural skepticism abounded. Societal narratives- religious, political, and philosophical, were now treated with suspicion. Because there was nothing left to believe in, truth, goodness, and beauty became relative.

There were no more absolutes, and beauty became viewed as something that exists purely in the eye of the beholder, not in reality. Meaning itself, could not be trusted.

This new post-modern philosophy culminated in the building of a new cultural center for Paris; one that would embody openness, experimentation, and modernity. It was named “The Pompidou”.

The building itself was built inside out, with all its ductwork and piping on the outside of the building. It makes no claim about beauty as an objective reality.

There is no meaning embedded, inherited, or revealed.

Instead, it is left open to interpretation- a perfect reflection of a faithless culture committed to the idea that objectivity is oppressive, and that beauty only exists in the mind of the beholder.

The Journey

The pre-modern era taught that beauty was discovered. The modern era taught that beauty was created. And the post-modern era teaches that it doesn’t exist at all.

All three philosophies captured perfectly within walking distance: Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower, and the Pompidou. A 2.7-mile stroll will take you by all three.

It’s the same walk that humanity has been on for the past millennia. A journey from faith, to reason, to meaninglessness.

But a journey is not a destination. Paths can be retraced. Perhaps the task before us, is not to invent a new definition of beauty, nor to abandon the search altogether, but to recover the humility to believe that beauty still waits to be found.